Throughout this paper, a random variable will be a measurable function

from a probability space to some Banach space (often the real

line). The norm in the implicit Banach space will always be denoted by

![]() .

.

Suppose that

![]() is a non-increasing

function. Define the

left continuous inverse to be

is a non-increasing

function. Define the

left continuous inverse to be

In describing the tail distribution of a random variable ![]() , instead

of considering

the function

, instead

of considering

the function

![]() , we will

consider its right continuous inverse, which we will denote by

, we will

consider its right continuous inverse, which we will denote by ![]() .

In fact, this

quantity appears very much in the literature, and is more commonly

referred to as the decreasing rearrangement

(or more correctly the non-increasing rearrangement)

of

.

In fact, this

quantity appears very much in the literature, and is more commonly

referred to as the decreasing rearrangement

(or more correctly the non-increasing rearrangement)

of

![]() . Notice that if one considers

. Notice that if one considers ![]() to be a random variable on the

probability space

to be a random variable on the

probability space ![]() (with Lebesgue measure),

then

(with Lebesgue measure),

then ![]() has exactly the same law as

has exactly the same law as

![]() .

We might also consider the left continuous inverse

.

We might also consider the left continuous inverse

![]() . Notice that

. Notice that

![]() if and only if

if and only if

![]() .

.

If ![]() and

and ![]() are two quantities (that may depend upon certain

parameters), we will write

are two quantities (that may depend upon certain

parameters), we will write

![]() to mean that there exist

positive constants

to mean that there exist

positive constants ![]() and

and ![]() such that

such that

![]() . We will call

. We will call ![]() and

and ![]() the constants of approximation. If

the constants of approximation. If

![]() and

and ![]() are two (usually non-increasing) functions on

are two (usually non-increasing) functions on

![]() , we will write

, we will write

![]() if there exist

positive constants

if there exist

positive constants ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() such that

such that

![]() for all

for all ![]() . Again, we

will call

. Again, we

will call ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() the constants of

approximation.

the constants of

approximation.

Suppose that ![]() and

and ![]() are random variables. Then the statement

are random variables. Then the statement

![]() is the same as the

statement

is the same as the

statement

![]() . Since

. Since

![]() for

for ![]() the latter statement is equivalent to

the existence of positive constants

the latter statement is equivalent to

the existence of positive constants ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and

![]() such that

such that

![]() for

for

![]() .

.

To avoid bothersome convergence problems, we will always suppose that

our sequence of independent random variables ![]() is of finite

length. Given a sequence of independent random variables

is of finite

length. Given a sequence of independent random variables ![]() , when

no

confusion will arise, we will use the following notations. If

, when

no

confusion will arise, we will use the following notations. If ![]() is a

finite

subset of

is a

finite

subset of

![]() , we will let

, we will let

![]() , and

, and

![]() . If

. If ![]() is a positive integer, then

is a positive integer, then

![]() and

and

![]() . We will

define the maximal function

. We will

define the maximal function

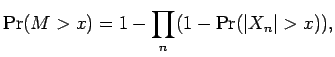

![]() . Furthermore,

. Furthermore, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the length of the sequence

is the length of the sequence ![]() .

.

If ![]() is a real number, we will write

is a real number, we will write

![]() and

and

![]() .

For

.

For

![]() , we will write

, we will write

![]() .

Similarly we define

.

Similarly we define

![]() ,

,

![]() , etc.

, etc.

Another quantity that we shall care about is the decreasing

rearrangement of the disjoint sum of random variables.

This notion was used by Johnson, Maurey,

Schechtman and Tzafriri (1979), Carothers and Dilworth (1988),

and Johnson and Schechtman (1989), all in the context of sums of

independent random variables.

The disjoint

sum of the sequence ![]() is the measurable function on the measure

space

is the measurable function on the measure

space

![]() that takes

that takes

![]() to

to

![]() . We shall denote the decreasing rearrangement of

the disjoint sum by

. We shall denote the decreasing rearrangement of

the disjoint sum by

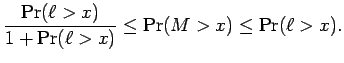

![]() , that is,

, that is,

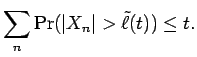

![]() is the least number such that

is the least number such that

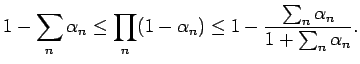

Proof: The first inequality follows easily

once one notices that both sides of this inequality are zero if ![]() .

.

To get the second inequality, note that, by an easy argument, if ![]() ,

,

![]() with

with

![]() , then

, then